Maggie Smith’s scene-terminating quips aside, the most delightful moments of a Downton Abbey episode occur when a character squints, bewildered and curious, at some mundane object or concept: Carson the butler ranks an electric toaster alongside the ordeal of “sheltering a dangerous revolutionary.” The Dowager Countess wonders, “What is a weekend?”

And suddenly, a fourteen-dollar kitchen appliance and two alarm clock-free days become exotic to us, too. New Yorker blogger Alexandra Lange notes that when it comes to technology on Downton Abbey, it’s the female characters who are the “chief users and beneficiaries” of it.

Women doing almost anything beyond the spheres of marriage and motherhood provoked controversy throughout the Victorian and Edwardian eras. Add in new technology or a social innovation, and the shock factor multiplied. Consider these four novelties from the 19th century:

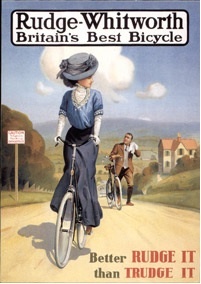

The Bicycle: Imagine pedaling a bicycle side-saddled. The author of an 1869 cycling guide does, describing a bicycle (or velocipede, as it was often called then) adapted to be suitable for ladies to operate.

He seems baffled as to why a lady would want to operate a bicycle when she could very pleasantly be a passenger on her husband’s, but as women seem determined to do so, he thus explains the required equipment and clothing. He concludes with a plea: don’t go riding in all-female groups. “Custom and nature revolt against it,” and it isn’t feminine.

Defenders of the bicycle admitted that possibly, the occasional “impure” woman had indeed cycled her way to the site of some immoral deed, but they roundly denounced any connection between cycling and Satan.

Croquet: This game probably puts you more in mind of linen suits and tea parties than Nike shoes and Gatorade, but did you know it was once (and only once, in 1900) an Olympic sport? The controversy of croquet was rooted in its popularity: in the 1860’s it was growing so rapidly that no one could agree on the rules. Croquet enthusiasts of the time lament the fact that players from different towns could hardly get through a game without heated arguments over the right way to play it.

But more importantly, croquet became popular at a time when Victorian society was considering the possibility that a bit of exercise for women might not mark the downfall of Western society after all. Couldn’t have them sweating, of course, but a game like croquet, even though it posed the risk of an exposed ankle here and there, was deemed appropriate for women.

Croquet gave us the earliest sports clubs that included women, as well as, according to Olympic Games historian Bill Mellon, the first female Olympians–competing alongside the men, no less. So if you’re a woman who’s ever taken it for granted that you could compete on a sports team or hit the gym after work, take a moment to thank croquet.

The Dishwasher: Josephine Cochrane invented the dishwasher because, it is said, she was tired of the servants breaking her expensive china. However, the fact she devoted the rest of her life to perfecting and promoting the machine suggests much more about her drive and intelligence than her concern for broken dishes.

At any rate, the only initial protests against the dishwasher came from workers displaced by the machine. Hotels and restaurants eagerly installed dishwashers, and Cochrane’s invention won a top award at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago.

It wasn’t until Cochrane tried to convince consumers they needed a family-sized version of the machine that she ran into real resistance. While some questioned the morality of taking women from their God-given duties as homemakers, the main issue was that women didn’t want it. It required more hot water than most households could generate, for one thing.

For another, it turned out that in the wide spectrum of housekeeping chores, washing dishes fell in the “somewhat pleasant” end. It would take decades and post-WWII consumerism to make the dishwasher a standard kitchen feature.

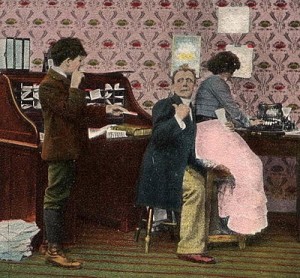

The Typewriter: It brought the usual bustle of Downton Abbey’s downstairs to a halt in Season One as the staff gathered round to gawk at Gwen the maid’s secret typewriter. In reality, the typewriter was no longer such a novelty in 1912. Though some worried the machine would depersonalize social correspondence (rather like some wonder today whether Facebook undermines our “real life” relationships), typewriters were just too simple and practical not to be quickly adopted.

The real controversy of the typewriter wasn’t the machine, but its effect. Historian Anna Davin compared the typewriter to the Trojan horse, bringing an army of female clerical workers into a city of men. By the time Gwen the maid is trying to break in, the number of female clerical workers has surged by almost 2000% over the space of a few decades.

In The Twelve Pound Look, a 1910 play by Peter Pan author J.M. Barrie, the price of a typewriter (£12) allows a woman to leave an unhappy marriage and support herself, as sensational a premise as Thelma and Louise was in its day. Some rejoiced in the earning opportunities this new technology offered women. Others were doubtful or just plain scandalized: Do women have the physical stamina to keep working hours? Won’t they be morally corrupted? Aren’t they taking jobs from the men they should be marrying?

The one sure thing: the typewriter made a new world of the workplace.